This week's update comes from Pierre Paul, cash management director

Despite a short-term set-back caused by the “pingdemic”, the UK economy is performing far better than many feared at the height of the pandemic. The UK economy is still not at pre-pandemic levels but vaccine rollout has led to greater consumer confidence, workers have been supported by the furlough scheme and businesses have received government support. This consumer confidence has increased demand but bottlenecks caused by the global aspect of the pandemic have led to a shortage in the supply of some raw materials and components; this in turn has led to rising prices and consequently rising inflation.

Historically the Bank of England would use monetary policy as its main tool to control inflation. The effect of raising interest rates would be to reduce demand which in turn would lead to lower prices and then lower inflation.

To raise rates now as the UK is still dealing with the pandemic would potentially derail the recovery, resulting in an even slower return to pre-pandemic levels of economic activity. So the Bank of England is minded to “look through” the current spike in inflation and focus on targeting 2% inflation on a two year horizon. Accordingly, any tightening of monetary policy will be well signalled and should not come as a shock to financial markets. To that end, the Bank of England has recently appeared to signal that interest rates are likely to rise next year which, on the face of it, is good news for savers. However, whilst interest rates might rise a little, they are unlikely to reach the dizzy heights of around 5% last seen in 2009 before the financial crisis.

The reason is technical and is a by-product of Quantitative Easing or “QE”.

QE refers to a bond buying programme initiated by the Bank of England in 2009 in response to the financial crisis. The loss of confidence meant that bonds held by banks fell in value but yields rose. Falling bond prices could lead to defaults and rising bond yields could slow economic activity. To prevent this from happening the Bank of England (and other Central banks: US, EU and Japan) started to buy government bonds held by banks.

The Bank of England financed these purchases by printing money. The outcome was that the Bank of England grew its balance sheet by owning these bonds and the cash used to buy the bonds was held by the banks to be used to finance mortgages and commercial loans which would support the housing market and stimulate economic activity.

QE has been a regular part of the Bank of England’s money market operations since 2009 and as a result the Bank now owns around £800 billion of government bonds, which has caused the Bank’s balance sheet to balloon since QE was introduced. QE is not intended to be permanent and in a speech on 5th August by Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England, he set out the conditions needed to reverse QE or as he put it “to reduce the stock of purchased assets”. As ever, Mr Bailey chose his words very carefully so as not to cause a “taper tantrum” and for that reason his speech was not particularly headline grabbing. In summary, he said that the Bank would begin reducing the stock of purchased assets at a time when the markets are functioning normally, in a way that provides a predictable and gradual path for the reduction in stock. Initially this would be by ceasing to reinvest the maturing proceeds of assets already held by the Bank, but which would not start until Base Rate has risen to 0.5%. This is lower than the previous threshold of 1.5% and is due to two things:

- The Bank’s belief that the effect of reducing QE will be less than previously thought; and,

- That setting a negative Base Rate is now part of the Bank’s monetary policy toolkit.

Mr Bailey then stated that the process of actively selling assets would not be considered until Base Rate had risen to at least 1% and would be conducted over a period of time so as not to disrupt the functioning of financial markets.

So, not a headline grabbing speech but one filled with caveats to soothe markets and if necessary delay the start of the tapering process.

The interesting part is that the Bank has reduced the level of Base Rate at which it will start QE tapering from 1.5% to 0.5%, which would suggest that QE tapering could start sooner than expected. However, it could also be taken as a signal that the Bank does not expect Base Rate to reach 1.5% in the foreseeable future.

One reason for potentially lowering the expectations of future Base Rate rises is that the Bank is mindful of the effect of raising Base Rate on the Government’s finances. It is estimated that a 1% rise in Base Rate will cost the Government £25 billion per annum on new debt. Given the recent shock of increase UK taxes and you can see why the Bank of England needs to tread carefully in case monetary policy tightening in turn caused a further need tighten fiscal policy.

So, the welcome economic recovery from the pandemic means we are unlikely to see negative interest rates but, on the other hand, political sensitivities mean that we are also unlikely to see a return to much higher rates in the short-term.

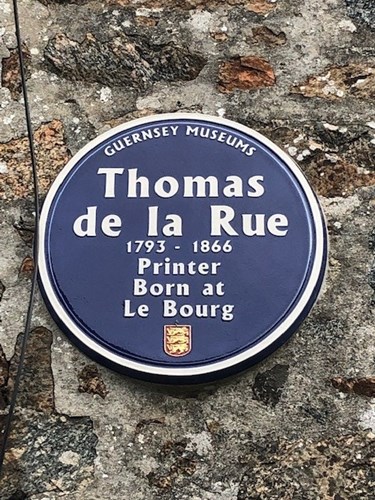

To round up this week, some history.... As you can imagine, the cash management team is interested in cash. On the gable wall of a shop in the parish of Forest in Guernsey is a blue plaque to mark the birthplace of Thomas de la Rue, founder of De La Rue plc, one of the world’s leading banknote printers. Born in Guernsey in 1793, Thomas de la Rue moved to the UK setting up a business which went on to patent an envelope making machine, gain a Royal patent to print playing cards and print early postage stamps before being retained by many countries to print their bank notes. Thomas de la Rue died in 1866 but the company which bears his name remains a major force in banknote technology.