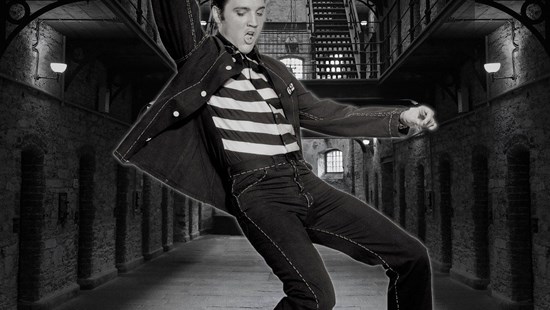

In 1977, just prior to “The King’s” untimely passing, 170 people were earning a living as Elvis Presley impersonators worldwide. Two decades later, their number had increased to 20,000 and experts were predicting that, by 2019, half the world’s population would be Elvis impersonators.

See what happened there?

Despite much of their output being as ill-conceived as the above (ridiculous, but genuine) example, the influence of “expert” predictions on investors’ behaviour is arguably as powerful as it has ever been. Though by no means the only cause, much of the short-term volatility seen in financial markets is the result of investors’ response to the release of economic data or company results that fall outside the range of consensus estimates. All of which flies in the face of common sense, since to even the casual observer the quality of much of these experts’ work is, at best, pretty ordinary.

The reasons for that are numerous, but in many instances are behavioural factors, chief among which is the “herd mentality”: a fear of lifting one’s head over the parapet or the flip side of that coin - the comfort of being wrong in groups - means that forecasts can be slow to change, despite evidence to the contrary. “Anchoring” – a reluctance to depart too far from the previous data point, or even just sheer laziness/uselessness (I’ll just have a look at what my peers are doing) also prevail. Then, as with our example above, there’s the blind extrapolation of a trend to a clearly unreasonable conclusion, but, hey, that’s what the numbers are telling us!

To complicate matters further, the methodology behind economic data is itself far from straightforward. Take, for example, US GDP figures. Due to the way in which the raw data is collected or submitted and the timescale over which this information is collated, there are actually three official quarterly announcements: a preliminary estimate, a revised estimate and the final figure. Other data series are routinely updated in the same way. As history shows, these numbers can change meaningfully (and not necessarily in the same direction), particularly when extraneous influences are involved – the volatility in levels of activity due to post-pandemic supply chain disruptions being cases in point. At each stage of this process, however, there remains the likelihood of a knee-jerk reaction from investors when / if each of these releases does not match the consensus estimate.

And then there’s China! Although there is an almost universal acceptance that the accuracy of China’s official economic reports is, to say the least, questionable, Mr Market is still prone to respond impulsively when the announcement of an imaginary number doesn’t meet analysts’ prediction of that imaginary number. Einstein’s (alleged) definition of madness – doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different outcome – springs to mind.

Whatever the reasons (and there are many more), numerous academic studies have shown that the predictive record of economic forecasters and corporate analysts is, generally speaking, woeful (there are, of course, individual exceptions). And yet, time and time again, investors will be compelled to reach for the buy / sell button, fire up the trade blotter, call their broker or advisor, or send off that e-mailed instruction in response to the latest “important” economic or corporate announcement.

Within an environment in which animal spirits are rife and bouts of volatility a seemingly permanent fixture, maintaining a focus on enduring secular themes, whilst also keeping a weather eye on the global economy’s position in the long-term cycle, means that we are able to filter out the market noise and distractions that are a function of the behavioural tendencies described above. Experience suggests that avoiding the jeopardy (and costs!) inherent in a short-term trading mindset are far more likely to result in superior investment performance over time.